Accelerometers are a type of sensor used by mobile developers to sense the movement of a device for the purpose of user interface control.

Nearly every mobile device – including your smartphone, tablet, fitness tracker, and smartwatch – contains an accelerometer that can measure the proper acceleration force of an object (i.e., the rate of change of velocity).

When you rotate your iPad 90 degrees and the screen automatically rotates to the new angle, the accelerometer is helping to sense the change and trigger the adjustment to your display. When your FitBit tracks the number of steps you take, the accelerometer is sensing movement of the device, which is used by an algorithm to determine if the movement matches the pattern of your gait. These are examples of accelerometers being used to sense movement for the expressed purpose of applications, however, the accelerometer senses all movements of the device, (and thus, the person carrying the device).

Essentially, you are carrying one or more motion sensors on you at all times. While the type of sensors are different from wearing a motion capture suit used in filmmaking or video game development, the same principle is at work, with sensors capturing data about your movements. As you can imagine, accelerometers generate a lot of data about the movement of your devices. From this movement data, inferences can be drawn about the behaviour of the device carrier.

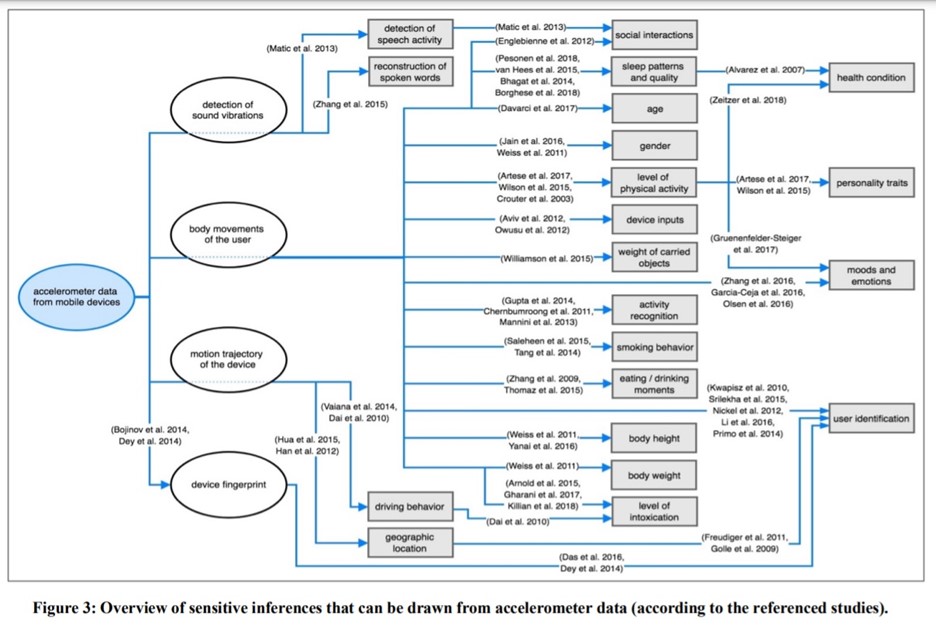

Three researchers at Technische Universität Berlin, Jacob Kröger, Philip Raschke, and Towhidur Bhuiyan, wanted to better understand the inferences that could be drawn from accelerometer data. Through a review of experimental studies on accelerometer data, they outlined how inferences could be drawn about a user’s:

- Activities

- Location

- Body Features

- Identity

- Age

- Gender

- Health

- Mood

- Emotions

- Personality

That is an incredible list. The ability to infer that a user is psychologically stressed from the movement his or her iPhone speaks to the precision of accelerometers and the power of data analysis.

See the diagram below for an overview of how accelerometer data from device sound vibrations, movement, and trajectory can be used to draw inferences about a user (and the studies that identified these capabilities).

These findings have serious implications for user privacy. As Kröger, Raschke, and Bhuiyan note in the paper, user protection for accelerometer data is lacking, largely due to the lack of understanding of the issue. In current mobile operating systems, third-party applications can access accelerometer data without requiring any permission or conscious participation from the user.

With other forms of data collection such as audio and video, there is a more obvious method of private information collection, and so explicit user permission is typically required to access data.

With accelerometer data, a user may be indifferent as to whether or not the movements of a device are being tracked. Once they understand that these movements can be used to infer that they smoke cigarettes (the cadence and distance of wrist movements), to determine their smartphone’s PIN (the movement of keystrokes on the screen), or their personality (movements, posture, and hand gestures), the necessity for user privacy standards should be apparent.